Those bundles of joy cost bundles of money, so Victoria Whipple, a quality control worker at Kumho Tire in Macon, Ga., had been working overtime to get ready for her new arrival.

She also got involved in union organizing at the plant, and management decided to teach her a lesson. It didn’t matter that Victoria had seven kids ranging in age from 10 to 1. Or that she was eight months pregnant. Those things just made her a more appealing target.

She also got involved in union organizing at the plant, and management decided to teach her a lesson. It didn’t matter that Victoria had seven kids ranging in age from 10 to 1. Or that she was eight months pregnant. Those things just made her a more appealing target.

On Sept. 6, the day Kumho workers wrapped up an election in which they voted to join the United Steelworkers (USW), managers pulled Victoria off the plant floor and suspended her indefinitely without pay solely because she was supporting the union. In a heartbeat, her income was gone.

“It kind of stressed me out because of the bills,” she explained.

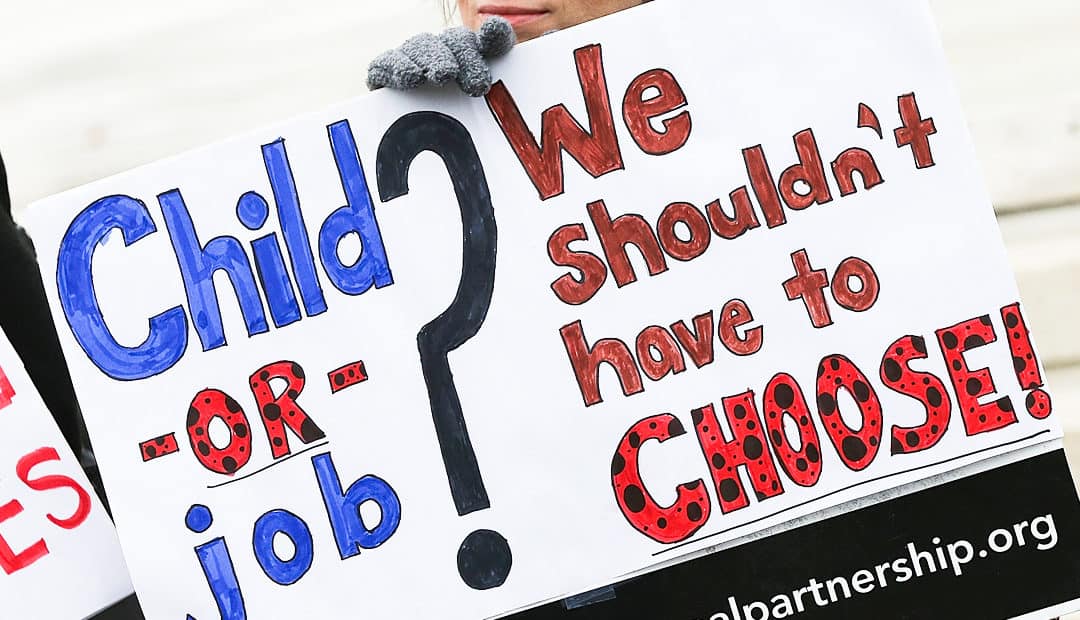

What happened to Victoria happens all the time. Employers face no real financial penalties for breaking federal labor law by retaliating against workers during a union organizing campaign. So they feel free to suspend, fire or threaten anyone they want. Workers are fired in one of every three organizing efforts nationwide, and the recent election at Kumho was held only because the company harassed workers before the initial vote two years ago.

Legislation now before Congress—the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act—would curtail this rampant abuse.

The PRO Act would fine employers up to $50,000 for retaliating against workers during organizing campaigns. It would require the National Labor Relations Board to go to court to seek reinstatement of workers who are fired or face serious financial harm because of retaliation, and it would give workers the right to file lawsuits and seek damages on their own.

The House Committee on Education and Labor has taken up the PRO Act, and it’s important that members of Congress understand exactly what’s at stake: families like Victoria’s that might be only a couple of missed paychecks away from financial ruin.

They can’t afford to be pawns in a company’s sordid union-busting campaign.

Victoria began working at Kumho a year and a half ago, after being laid off from her dispatching job at a distribution center. Her husband, Tavaris Taylor, recently started an over-the-road trucking job. They didn’t have much of a financial cushion for emergencies, and the suspension put their backs against the wall.

Instead of focusing on her family in the final weeks of her pregnancy, Victoria had to worry about money. It wasn’t healthy for her or her unborn child. And it wasn’t right.

When Victoria’s eldest child asked why she wasn’t going to work anymore, she just said she needed some time off. It would be wrong to burden a 10-year-old with the truth.

Victoria began borrowing gas money from her mom. She cut back her spending. She prioritized the bills and paid only those—rent, electricity and so on—that she considered absolutely essential.

She kept going to her doctor appointments, hoping the company’s insurance still covered her or that Medicaid would kick in if it didn’t. Victoria qualifies for Medicaid even though she works full time. The need for better pay is just one reason Kumho workers voted to join the USW.

But Victoria’s main concern was giving workers a bigger voice in the workplace. She went to a union meeting and thought: “Maybe representation would help.”

That’s how she became a union supporter—and got crossways with a company that couldn’t care less about its workers, their families or federal labor law.

Victoria didn’t know how long her suspension would last or if management’s next step would be to fire her. That would be Kumho’s kind of baby gift.

Then, out of the blue last week, a manager called Victoria and told her to return to work. On Friday, her first day back after two weeks without pay, managers had the brass to ask her if she understood why she had been suspended.

Yeah, she understood all right.

Companies will do almost anything these days—even suspend a pregnant woman and escort her from the premises—to keep out unions and hold down workers. That’s especially true of Kumho. Its egregious union-busting activities derailed workers’ attempt to join the USW two years ago.

Back then, Kumho threatened union supporters’ jobs, interrogated employees about their union allegiance, threatened to shut down the plant if the union was voted in and made workers think they were being spied on. The conduct was so extraordinarily bad that an NLRB administrative law judge ordered Kumho to assemble the workers and read a statement outlining the many ways in which it had violated their rights and federal labor law.

The NLRB also ordered this month’s election, in which workers voted 141 to 137 to join the USW. Thirteen challenged ballots will be addressed at an upcoming hearing.

The mistreatment of Victoria shows that Kumho hasn’t changed its ways over the past two years. Unfortunately, employers have no incentive right now to follow the law.

The PRO Act would help to level the playing field. Besides fining companies for retaliation and giving workers the right to sue, the legislation would prohibit employers from holding mandatory anti-union presentations like the “town hall” meetings Kumho forced Victoria and her co-workers to attend. Employers conduct the meetings to bully employees into voting against a union.

The legislation also would provide new protections once workers voted for representation. For example, if a company dragged its feet during bargaining for a first contract, a regular ploy to lower worker morale, mediation and arbitration could be used to speed the process along. And the PRO Act would prohibit employers from hiring permanent replacements for striking workers.

Members of Congress need to understand something. Workers aren’t looking to pick fights with their employers. They just want to do their jobs well, work in safe environments and earn enough money to care for their families. And some companies work productively with unions, including the USW, to improve working conditions and product quality.

But employers like Kumho too often exploit their employees and resist any effort that workers make to improve their lot. When that happens, workers like Victoria will stand their ground. Now more than ever, they need the protections of the PRO Act backing them up.

What is the current status of the PRO Act? I'd never heard of it before this article.

"Legislation now before Congress—the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act—would curtail this rampant abuse." This is good, but under Trump/Republicans I assume it has no chance of passing. What else can be done under existing law?