L-R: Alan Greenspan, Paul Volcker, Ben Bernanke. Photo credit: U.S. Federal Reserve / cc

The obituaries for Paul Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chair who died December 8 at age 92, almost all echoed a noble, even heroic narrative. Between 1979 and 1987, as one prominent obit pronounced, Volcker’s bold and sweeping interest rate hikes shocked “the U.S. economy out of a cycle of inflation and malaise and so set the stage for a generation of prosperity.”

But prosperity for who?

Economist Gabriel Zucman has just delivered the most telling answer yet.

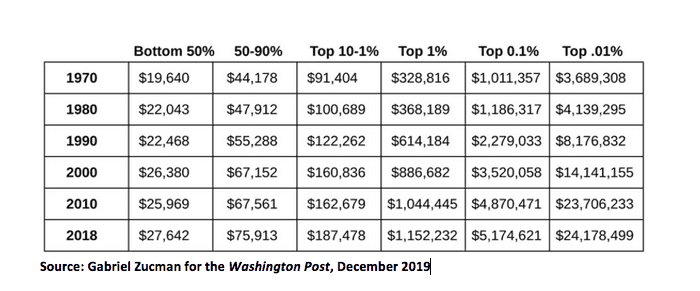

In a special analysis prepared for the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent, the University of California at Berkeley scholar has compared current average American incomes — in six different income ranges — to average incomes at the start of every decade since 1970.

Zucman’s income figures take into account both the taxes Americans pay federal and state governments and the transfers — everything from Social Security checks to veteran assistance — that go from government to individual Americans. In other words, his new breakdown shows what Americans had left in their wallets after paying their taxes and pocketing their benefits.

Some Americans, the new numbers show, had much more left than others. Phenomenally more. For America’s richest, the past half-century could hardly have been more prosperous.

In 1970, the nation’s top 1 percent netted $328,816, in today’s dollars. By 2018, that top 1 percent average had more than tripled, to $1,152,232.

But the most striking after-tax, after-transfer gains have gone to Americans even higher up in the economic pecking order. Average top 0.1 percent incomes have more than quintupled since 1970, from just over $1 million to over $5 million. Average top 0.01 incomes have jumped over six-fold, from $3.7 million in 1970 to $24.2 million in 2018.

In essence, America’s very richest — the top one-hundredth of our top 1 percent — have on average added about $427,000 to their incomes every year since 1970.

The bottom 50 percent of Americans have added to their incomes, too —on average, a measly $167 a year.

And what about Americans in between that bottom 50 percent and the top 1 percent? The vast majority of those in-betweeners haven’t seen any prosperity jolt either. Those in what researchers call the “middle 40” — the 50 to 90 percent income cohort — averaged $75,913 last year, up 72 percent from their $44,178 average in 1970.

And what about Americans in between that bottom 50 percent and the top 1 percent? The vast majority of those in-betweeners haven’t seen any prosperity jolt either. Those in what researchers call the “middle 40” — the 50 to 90 percent income cohort — averaged $75,913 last year, up 72 percent from their $44,178 average in 1970.

That sounds not half bad, until you figure in the major financial challenges that have emerged over the past 50 years, the skyrocketing costs of big-ticket items like homes and college educations. House prices, for instance, have more than doubled since 1970, after taking inflation into account.

“Middle 40” households are also shelling out significant dollars for expenses that simply didn’t exist in 1970. Back then, most American households paid nothing for the television programming they watched. Rabbit ears on their TV sets brought them that programming for free. Now households pay cable companies for what they watch.

The online world, of course, didn’t exist in 1970 either. With this world’s emergence have come significant new expenses for Internet access, computer hardware, and smart phones.

Now we do, to be sure, gain considerable benefit from all these new expenses. But that doesn’t make these new outlays any less onerous. We cannot, after all, freely choose to do without the new tech products and services that surround us. To participate fully in modern American life, we have to partake.

European social scientists have a phrase for the sociological dynamic at play here. They see poverty as “social exclusion,” the incapacity to lead the life that most of society considers minimally decent. If you can’t afford that life, you stand excluded, always on the outside looking in, with all the stress that falls upon those with outsider status. Most households on the economic edge do everything they can to avoid that exclusion.

And that often means — in the United States — going deeply into debt because incomes for the bottom 90 percent have simply not kept pace with the growing financial burdens of modern life. Gabriel Zucman’s latest income calculations make all of this plainer than ever before.

Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org. His recent books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win: The Forgotten Triumph over Plutocracy that Created the American Middle Class, 1900-1970. Follow him at @Too_Much_Online.

My gut answer to your title question is, "No!"

I submit that question was not answered in this article.

More pertinent might be, "Is the U.S. ripe for an economic class-based civil conflict?" How else can the nation break out of its plutocratic quagmire, with its guarantee of inescapable poverty for its majority, who are, supposedly represented by their peers in our Democracy?