Fifty-one years ago, thousands of Americans gathered for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Today, events in Ferguson, Mo., and North Carolina show how much work remains, and how we can carry on the mission of the March.

America has made tremendous progress since thousands marched for “civil and economic rights”, and Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his famous “I Have A Dream” speech before the Lincoln Memorial. As I wrote last year, on the fiftieth anniversary, we have undoubtedly come a long way:

- We are more educated. Seventy-five percent of African-Americans complete high school now, compared to 15 percent in 1963. There are 3.5 times more African-Americans attending college, and five college graduates for every one in 1963.

- Fewer of us live in poverty. The number of African-Americans living in poverty has declined 23 percent since 1963.

- More of us are homeowners Fourteen percent more African-Americans are homeowners than in 1963.

However, as I wrote last week, the unrest in Ferguson, in the aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown again revealed how far we have yet to go:

- Black wealth has declined. The racial wealth gap nearly tripled between 1984 and 2009. The recession widened the gap. Black household wealth dropped 53 percent, compared to a 16 percent drop for white households.

- Black poverty is disproportionately high. According to the US Census Bureau, the poverty rate for African-Americans is 26 percent — more than twice the 11.6 poverty rate for whites.

- Blacks are more likely to be unemployed. The black unemployment rate is consistently double that of whites.

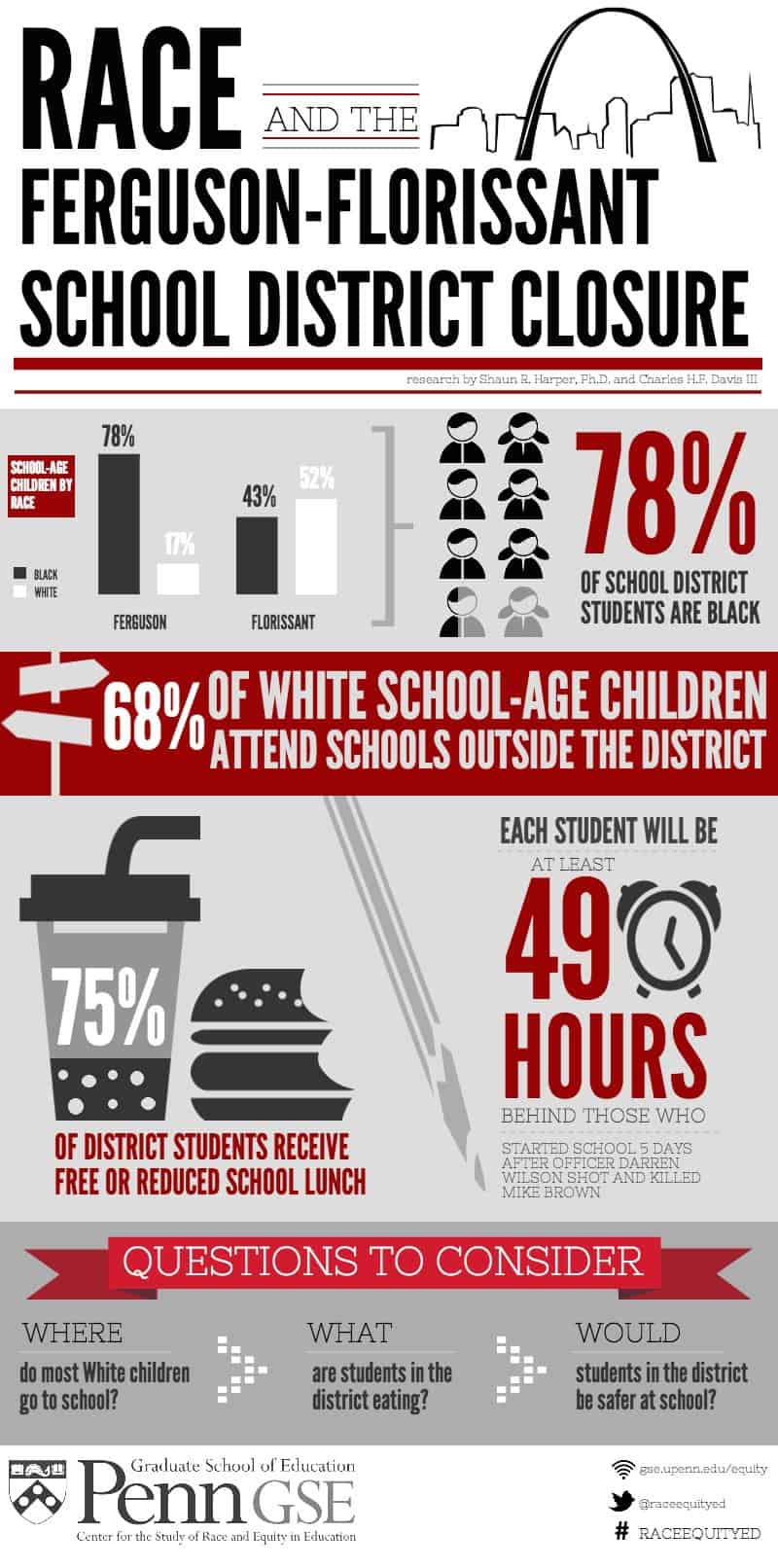

- Our children still attend segregated, poorly funded schools. Seventy-four percent of black students attend segregated schools; 38 percent attend “intensely segregated” schools — with just up to 10 percent white students. Since a 10 percent increase of non-white students in any school is associated with a $75 decrease in per student spending, those schools are often poorly funded.

The shooting of Michael Brown turned a spotlight on a city where racial disparities illustrate how “civil and economic rights” are inextricably linked. A suburb of St. Louis, Ferguson was mostly white until most white families moved further out to escape school desegregation, creating what Jeff Smith of the New York Times’ described as “a ring of mostly middle-class suburbs around an urban core plagued by entrenched poverty.”.

The result is a city once ranked the 9th most segregated in the country, and bitterly so. It is 67 percent black, yet its power structure is overwhelmingly white, symbolized by a police force that’s 95 percent white. It’s a city so poor that it relies on court fees — resulting for one-quarter of its revenue. In a town where 86 percent of traffic stops, 92 percent of searches, and 93 percent of arrests were of black people, Smith writes that it means “struggling blacks do more to fund local government than relatively affluent whites.”

The consequences are clear in Ferguson’s schools, where University of Pennsylvania researchers found stark disparities.

In the context of Ferguson’s racial disparities, it’s understandable that the shooting of Michael Brown, and the police department’s paramilitary response to protests sparked anger in the streets. Dr. King said three years after the March on Washington, “a riot is the language of the unheard.” At Brown’s funeral, Rev. Al Sharpton gave voice outrage at an American that invests more in military weapons than youth like Michael Brown:

“America is going to have to come to terms when there’s something wrong, that we have money to give military equipment to police forces, when we don’t have money for training, and money for public education and … our children.”

Today, Dr. King might be dismayed that the streets of Ferguson in the last few weeks resembled scenes witnessed more than 50 years ago. Yet, even in the midst of Ferguson’s unrest, voter registration drives signal the beginnings of change.

King would find hope and inspiration in Raleigh, North Carolina — more than 800 miles west of Ferguson — where the Moral Mondays movement’s “Moral Week of Action” culminates today — the anniversary of the March on Washington — with a “Jericho March” to the North Carolina State Capitol.

For seven days, activists led by Rev. Dr. William Barber Jr. marched, sang, prayed, and demanded social and economic justice, in the spirit of those who marched on Washington 51 years ago. Like the protests of the Civil Rights Era, it has spread far beyond North Carolina, and beyond the south. Social justice coalitions in twelve states held their own weeklong events: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.

As we reflect upon the March on Washington, events in Ferguson are a sober reminder of how far we have yet to go to fulfill its goals. Yet, the Moral Mondays movement reminds us that the road to finishing the March runs from Ferguson to Raleigh, and beyond. We have but to begin.