On Saturday, thousands came to Washington, to walk in the footsteps of those who came to the capital 50 years ago, for the "March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom." The event became an iconic moment for the African-American civil rights movement and set the mold for many movements to follow. This 50th anniversary is an occasion to celebrate how far we have come, and recognize how far we have left to go.

This Wednesday, President Obama will stand where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stood 50 years ago and delivered his famous "I Have A Dream" speech. The president's task will be far different from Dr. King's. Seen by many as a living embodiment of Dr. King's dream, Obama will face the challenge of mapping out a path to delivering on the economic aspects of Dr. King's unfulfilled dream, and beginning to lead the nation down the path to economic justice.

Full employment is one of the biggest unmet demands of the 1963 march. Four of the ten formal demands delivered by march director Bayard Rustin on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 concerned employment.

What else could calling for "a massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers — Negro and white" be except a demand for full employment? And a "national minimum wage act that will give Americans a decent standard of living," is the equivalent of a present-day demand for livable wages?

While the other demands of the 1963 march concerning education, housing, and voting rights are (disappointingly) just as relevant and urgent today as they were 50 years ago, the biggest challenges facing African Americans are high rates of unemployment and underemployment. When President Obama takes to the podium, his challenge will be to spell out how American will begin to address these twin crises.

Come A Long Way

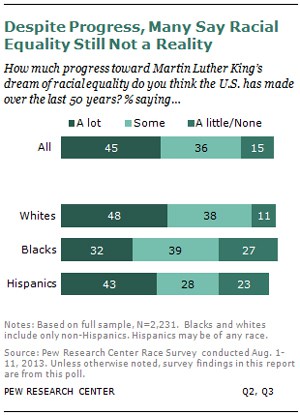

Americans are in agreement that Dr. King's dream remains unfulfilled. Most Americans say that that racial equality is still not a reality. But delving deeper into those numbers reveals stark divisions on the subject. According to a Pew Research Center poll fewer than one in three blacks, and fewer than half of whites say that the U.S. has made "a lot" of progress towards achieving racial equality.

Americans are in agreement that Dr. King's dream remains unfulfilled. Most Americans say that that racial equality is still not a reality. But delving deeper into those numbers reveals stark divisions on the subject. According to a Pew Research Center poll fewer than one in three blacks, and fewer than half of whites say that the U.S. has made "a lot" of progress towards achieving racial equality.

Growing up in the South, and being raised Baptist, I grew up singing many of the songs of the civil rights movement. Reflecting now upon the progress made in the last 50 years, I can't help but recall how many of those songs — from "Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around" to "Guide My Feet," and Dr. King's favorite "Precious Lord, Take My Hand" — speak of long, arduous journeys; of progress made and miles yet to go.

Black America has come a long way since August 1963. We are a far more educated people than we were 50 years ago. Seventy-five percent of African Americans complete high school now, compared with just 15 percent 50 years ago. There are now 3.5 times more African Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 enrolled in college than there were 50 years ago. Five African-American college graduates for every one graduate in 1963.

Gains in education have led to an increase in standards of living. The number of African-Americans living in poverty has declined 23 percent since 1963. Fourteen percent more African-Americans are homeowners than in 1963.

Just as the old spirituals spoke of long journey, the also spoke of valleys to be crossed and mountains to be climbed. The numbers above may represent mountaintops reached by many African-Americans in the last 50 years, they also make clear the valleys and mountains that lay between us and the "promised land."

A Long Way To Go

Gains in education have not been enough to close the unemployment gap between black and white Americans. In fifty years, it has narrowed just 6 percent, and current unemployment trends threaten to widen it from a broad gap to a yawning chasm. The income gap, which has only closed 7 percent since 1963, suggests underemployment is as great a challenge as unemployment.

High rates of unemployment and underemployment among African-Americans have contributed to other disparities which remind us that "the Dream" has not been fulfilled, and the demands of the 1963 march have not been met. The wealth gap between black and white Americans has persisted, and worsened during the most recent recession, when net wealth for African-Americans dropped 27.1 percent. White families now record wealth six times greater than blacks. Disproportionate poverty also persists. Just 13.8 percent of the population, African-Americans account for 27 percent of Americans living in poverty.

Epidemic unemployment has kept black unemployment rates nearly double the rate for white Americans. This year, the unemployment rate for African-Americans has averaged above 13 percent. The black unemployment rate is consistently twice that of whites.

Today, roughly one in five black workers are underemployed. This means that 22.4 percent of African-American workers either (a) work part time but are able and willing to work full time; or (b) are willing and able to work, and have looked for work for a year or more, but have given up actively seeking employment.

Why, despite the progress made since 1963, have disparities persisted? Many of the contributing factors are depressingly familiar on this anniversary. A 2005 study identified discrimination as the root of the black unemployment crisis. After sending black and white male job applicants out with identical resumes the researcher found that not only were white applicants more likely to be hired, but that even giving white applicants' criminal backgrounds didn't make them less likely to be hired than their black counterparts.

A college degree doesn't make it any easier for black applicants to get jobs. African-Americans have greatly increased educational attainment, but college-educated whites are still more likely to get good jobs than college-educated blacks. Meanwhile, black workers are less likely to be in a good job,

Race remains such a significant obstacle in finding employment that black applicants resort to desperate measures, like scrubbing resumes clean of any details that might reveal their race to prospective employers. Others have found that having a "black-sounding" name is an obstacle to getting a job.

Conservative attacks on the public sector have imperiled even the few good jobs available to African-Americans. The lack of available good jobs in other sectors contributed to African-Americans being over-represented in the public sector. Now, as budget cuts force local and state governments to clash jobs, black workers are hit hardest as the public sector sheds jobs.

What's left is often low-wage jobs in the fast food and/or retail industries, that don't pay workers enough to afford basics like food, shelter, and medical care. It's no coincidence that the overwhelming majority of low-wage workers who protested for livable wages in cities like New York, Milwaukee, and Washington, Seattle, Chicago, and Detroit were black and/or Hispanic.

The Way Forward

President Obama faces a challenge when he speaks on Wednesday. It's not living up to the poetic rhetoric of Dr. King. Obama plays a much different role that King, but one that could easily burden him with the false need to fill King's shoes, as his person and presidency have come to symbolize a kind of fulfillment of Dr. King's dream.

President Barack Obama speaks during the dedication of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, Sunday, Oct. 16, 2011.

Yet, as president, the moment calls Obama to present and advocate policies that can eliminate the persistent disparities mentioned above. He may not be the president to take America to the "mountaintop" of full employment, but as with universal coverage and health care reform, Obama can be the president who get us closer to that next summit, by fighting for "a massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers." Or President Obama can move two million of into the middle class, by simply signing an executive order requiring that jobs financed by federal funds pay living wages.

Unemployment and underemployment were the themes of the National Town Hall Meeting on Poverty and Economic Empowerment, sponsored by the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) and Rainbow PUSH, which I attended on the eve of Saturday's march. Moderator Julianne Malveaux bean by reminding the audience that Dr. King was an "anti-poverty activist," and panelists — including Rev. Jesse Jackson, SCLC CEO Charles Steele, Judge Penny Brown Reynolds, Rev. Frederick D. Haynes III, scholar Darnell Moore, Rev. Otis Moss III, and author and scholar Obery M. Hendricks — focused on unemployment and underemployment as issues left outstanding.

Full employment and livable wages were, according to the panelists, essential to the economic justice envisioned by King, and demanded by the marchers in 1963. Judge Penny Brown Reynolds offered a definition of economic injustice that suggests a starting point for President Obama's speech on Wednesday. Judge Brown Reynolds defined economic injustice as "when the state sanctions activities and structures that do not meet the needs of the people."

As definitions go, it's a good one, and a good place to begin. Getting the government to cease being the biggest creator of low-wage jobs would be a good first step towards the state ceasing to sanction structures and activities that do not meet the needs of the people, and beginning to address the specific needs of African Americans for good jobs and livable wages.