Far-right radicals have made North Carolina the place to test their most extreme ideas. They redrew our voting maps, disempowered Black voters, shredded our safety net and are trying to pit rural and working people against each other. They rewrote the rules to benefit the rich and powerful at the expense of North Carolina’s poor and disenfranchised people.

Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

We founded Down Home North Carolina in 2017 to build a different future for our state. We believe a progressive vision for North Carolina must include all of us, including rural communities, if we are to counter the influence of far-right donors who have captured our state government.

Far-right ideologues like Art Pope have flooded our state with money, stoking racial resentments. They did this to engineer a right-wing supermajority in our State House, which they won in 2010, then took over the governorship in 2012.

We watched as they kicked voters off the rolls and used issues like gay marriage to drive a wedge between urban and rural voters. But we also knew this rightward shift was underpinned by longer-term trends. This was also the result of a major economic transition, and a hunger for change that was manifested in both parties.

Hollowed Out

North Carolina’s economy, especially in rural areas, has been hollowed out: our once-proud textile industry is almost gone. Farmers are struggling, and many middle-income jobs have left the state for good. This has left a lot of working people feeling government doesn’t care for them at all.

Republicans saw this opportunity, and ran with it. They also took advantage of a void left by Democrats, who have systematically under-organized in rural areas for decades. This left a lot of power on the table and let right-wing incumbents go unchallenged. Rural voters have rightly felt their voices were not being heard.

So we decided to step in, meet rural communities where they are, and see how their struggles can be addressed as part of a broader progressive movement.

Talking to Neighbors

We wanted to know what struggles and solutions mattered to rural working class families of all races, so we started by going door to door in two counties in North Carolina’s center and mountain west: Alamance and Haywood.

Outside the courthouse in Graham, the seat of Alamance County, there’s a Confederate monument that marks the site where a prominent Black political leader, Wyatt Outlaw, was lynched in 1871. White supremacists have rallied on the spot in recent years. We knew that racial oppression and distrust were deeply rooted in the history of this community..

But to know the history of North Carolina is to know that ways that race has been used to pit poor people, black, white, and brown, against each other. So long as we continue fight each other, we won’t be able to unite around our shared needs.

If we plan to take on the rich and powerful folks who benefit from our poverty, we’ll need to know what issues can unite people across race. So we went out to talk to our neighbors.

What Really Matters To Carolinians

We knocked on more than 4,000 doors in these two counties, to find out what issues matter most to rural working people. “No one’s ever asked me before” is what we heard over and over again, so that’s what we titled the report of our findings.

The first thing we discovered is that there’s far more unity among working-class residents, of all races, in small-town North Carolina than you might expect.

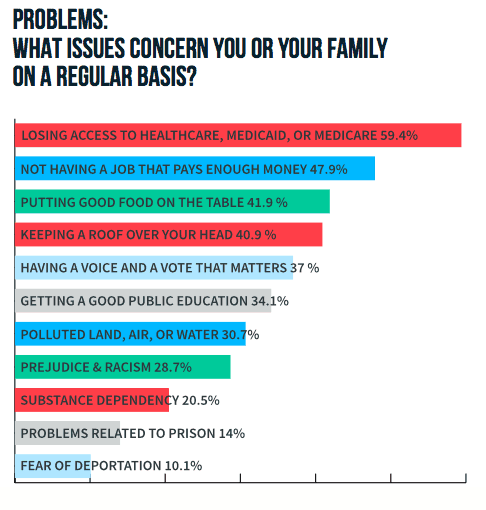

The number one concern of nearly everyone we spoke with was losing access to health care, followed by not having a good job that pays enough money to live. More than 40 percent say the worry regularly about “putting good food on the table” and “having a roof over your head.”

“I’m struggling just like everyone else is,” said Sam Wilds in Canton, in Haywood County. "There are a lot of people that don’t have a job — they have skills but they don’t have anywhere to use them because they don’t have options. Most folks do what they have to do to survive around here.”

Sam Wilds, Canton NC. Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

In terms of who small-town Carolinians hold responsible, the winner – hands down – is President Trump. But there are significant differences by race here: two-thirds of Blacks and Latinx singled out Trump, while only a third of white respondents did. This finding demonstrates the power of racist appeals and their ability to divide poor and working people along color lines.

Nearly everyone we spoke with disclosed a deep-held mistrust of government’s willingness or ability to address their concerns, whether Federal, state or local. At the same time, we heard that people want someone to speak up on their behalf, not just for big corporations or the wealthy.

Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

Many people still seem to believe that government can be a force for good in their lives, despite their experience to the contrary.

One in five black respondents cited problems relating to prison as a regular concern, while two-thirds of Spanish-speakers identify “racism and prejudice” as a regular problem; that’s twice as many as both white and Black respondents.

Finding Solutions

When it comes to solutions, that’s where the real consensus emerges. Two-thirds of respondents – of all races – cite better-paying jobs and healthcare as what will most directly improve their lives. Nearly half say overcoming racism and prejudice is a top priority, too.

Sam Malone, Waynesville, NC. Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

“I believe that we can figure out solutions from day to day about how we can make this world work better for everyone,” says Sam Malone, from Waynesville. “If we can figure out solutions to health care, to opioids, to giving people places to live, to making sure there are jobs, then we could make sure that no one is poor. "

What We Learned

What we learned most from talking with our neighbors in Alamance and Haywood counties is that we have ample reason to hope.

“I think I'm more shocked to know that we get along way more than the media would like to portray,” says Kischa Peña of Mebane in Alamance County. “I sat in homes with people that didn't look like me. I sat in homes with people who were older than me, who were younger than me. But we all have very similar issues. “

Kischa Peña, Mebane, NC. Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

Greensboro, where I live, is where sit-ins at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in 1960 helped bring about the end to legal segregation in this country. A century before that, North Carolina was home to the Red Strings, Quakers who resisted the Confederacy and sheltered slaves. Goldsboro is home to Rev. William Barber, whose Moral Mondays protests have now inspired a new Poor People’s Campaign to bring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of a just nation to fruition.

Pointing the Way

North Carolina is a beautiful state with a difficult history. But time and time again, North Carolina’s Black and poor communities have pointed the way toward a different future that includes justice for all. Democracy can work for working people here, if we can recapture the spirit of communal problem-solving that has been a part of our past.

Alamance and Haywood are just two small counties, out of a hundred in North Carolina, Still, we believe North Carolina’s redemption can start here: flipping power in these two small counties would be enough to end the right-wing legislative supermajority and would give working people a fighting chance to stand up and be heard.

Photo credit: Down Home North Carolina

Multi-racial, working class leadership is our best hope for a just future in North Carolina. As organizers, we have to meet people where they are, in their experiences of poverty and frustration.

We have to be ready to embrace visionary solutions to long-ignored problems. Sometimes it all starts with a conversation on someone’s front porch. That’s where we’ve started in North Carolina.