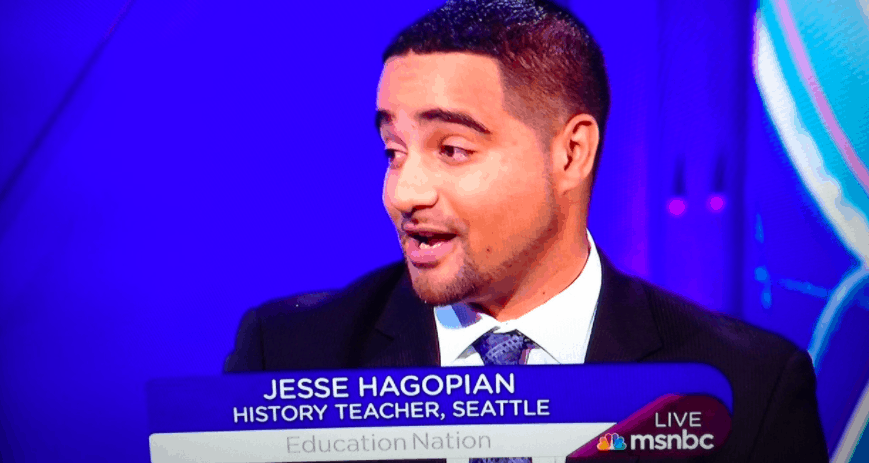

Seattle classroom teacher Jesse Hagopian wants to transform the school-to-prison pipeline into a school-to-justice pipeline for millions of Black and Brown students in American schools. He and thousands of his educator colleagues are taking strides toward that goal during the week of February 5 to 9 by staging a Black Lives Matter at School week of action in schools across the nation.

According to Hagopian, educators participating in the week of action - this year includes dozens of communities, including Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston - will wear Black Lives Matter shirts to school and teach lessons about structural racism, intersectional black identities, black history, and anti-racist movements.

"Too often the issues that matter most to students are absent from the curriculum," Hagopian tells me in an email. "Black students in this country face racism, and school has to be a place where they are supported to make sense of their world and be empowered to change it."

The idea for Black Lives Matter at School started in a Seattle elementary school, when a student support worker proposed devoting a day of teaching to issues of racial justice, and teachers in the school joined in solidarity. Inspired by that bold action, rank-and-file members of the union's Social Equality Educators group held discussions that culminated in a citywide Black Students’ Lives Matter event that over 3,000 teachers joined in support.

This year's nationwide effort, which has spread to cities including New York, Chicago, Boston, Baltimore and Rochester has been organized by a coalition of educators and civil rights activists.

These educators want more classrooms addressing the issues of police violence against Black youth, the problem of hate speech and racist political messaging, growing racial segregation in schools and housing, and “zero tolerance” school discipline policies that tend to disproportionally target Black students with overly-harsh punishments and out-of-school suspensions.

Black students are over three times more likely than White students to be suspended or expelled from school. Black girls are seven times more likely to be suspended than White girls. Students who have been suspended or expelled are three times more likely to come into contact with the criminal justice system the following year.

"Students talk all the time about the movement for Black lives, the increasing numbers of hate crimes, and social media hate speech they see around the country," Hagopian contends. "The question isn't, 'Are we going to let kids talk about issues of race and racism?' but rather, 'Are they allowed to talk about these issues in class with a caring adult?'"

Another issue important to these educators is the growing scarcity of Black teachers in the public school system.

Having just one black teacher in third, fourth or fifth grade significantly reduces the probability of low-income Black boys of dropping out of high school and increased Black boys and girls expectations of going to college. But the percentage of teachers in many big city school districts is in steep decline. From 2001 to 2012, the number of Black teachers in Philadelphia declined by 18.5 percent, in Chicago by nearly 40 percent, and in New Orleans, 62 percent.

In an article for The Progressive magazine, Hagopian quotes a study conducted by the Albert Shanker Institute that found since 2002 the total number of African American teachers decreased by 26,000, even as the overall teaching workforce has increased by 134,000.

The coalition behind Black Lives Matter at School also pushes for the teaching of Ethnic Studies in schools as a way to engage Black and Brown students in school curriculum.

"Traditional academics has been about studying the past as if Black people had not made significant contributions to our history," Hagopian insists. "The Black Lives Matter at School movement provides the space for educators around the nation to acknowledge the deficiencies of the corporate curriculum and encourages educators to teach about Black excellence, Black intersectional identities, and Black history."

A recent study by Stanford University researchers bolsters the case for Ethnic Studies in schools. In examining the impact of an ethnic-studies curriculum for struggling ninth-grade students in San Francisco high schools from 2010 to 2014, researchers found the classes boosted student attendance, grade point averages, and high-school credits.

Hagopian is not at all surprised an idea started in a lone Seattle elementary school is catching on nationwide. "Many educators, administrators, and parents know very well that our school systems don't support Black students."

Hagopian sees the Black Lives Matter at School movement as proof that collective struggle can make change. He notes that the demand for Ethnic Studies in Seattle turned into a coalition of activists, including the NAACP, that pressured the school district to convene a task force on the issue.

"This year I am teaching Ethnic Studies because of that movement," Hagopian says. "Seattle educators' action last year led to Philadelphia educators organizing for Black lives, and now this year, teachers all around the country have taken up the struggle.