It's hard to imagine a more relevant moment for the National Urban League to release its State of Black America 2013 report. This year, after all, marks the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington and the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation — two historical events of enormous importance to African Americans. It seems even more appropriate that the Urban League's report is released on the same day that President Obama — our first African-American president, recently re-elected to a second term — presents his annual budget to Congress.

Could there be a more appropriate moment to assess how far we've come, how far we've yet to go, and what kind of leadership is needed to move us forward?

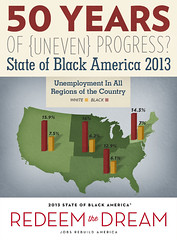

The subtitle of the report, "50 Years of {Uneven} Progress," acknowledges the undeniable progress since the 1963 March, and the remaining disparities that have worsened as a result of the financial crash, and the ensuing economic crisis and jobs deficit.

The impact of civil rights measures passed during the Civil Rights Movement, and the affirmative action programs policies that followed, is seen in the gains African Americans have made in education.

More African Americans complete high school. Only 15 percent of African-American adults today lack a high school education, compared with 75 percent of adults 50 years ago. This represents a 57 percent closure of the high school completion gap in 50 years.

More African Americans complete high school. Only 15 percent of African-American adults today lack a high school education, compared with 75 percent of adults 50 years ago. This represents a 57 percent closure of the high school completion gap in 50 years.- More African-Americans attend college. There are now 3.5 times more African-Americans aged 18-24 enrolled in college than were 50 years ago.

- More African-Americans hold college degrees. For every college graduate in 1963 there are now five.

Gains in education are tied to an increase in standards of living

- Fewer African-Americans live in poverty. Since 1963, the number of African-Americans living in poverty has declined 23 percent.

- Fewer African-American children live in poverty. The percentage of African-American children living in poverty has dropped 22 points in 50 years.

- More African Americans are homeowners. Since 1963 the percentage of African-Americans who own their homes has increased 14 points.

Those numbers tell the story of how far we've come. Yet they don't quite tell the story of where we are. First, they must be understood in the context of more data.

- The unemployment gap persists. The unemployment gap has only closed 6 percent since 1963, and the unemployment rate for African-Americans remains twice that of whites — regardless of education, gender, region of the country, or income level.

- The income gap persists. In 50 years, the income gap between African-Americans and whites has closed just 7 percent.

- The wealth gap is growing. Net wealth for African-American families dropped 27.1 percent during the recession.

- Disproportionate poverty persists. African-Americans make up 13.8 percent of the population, but account for 27 of Americans living in poverty.

As Isaiah J. Poole pointed out in his post, "The Sinking American Electorate: African Americans Still In Depression," the story these numbers tell is an old familiar one for African-Americans: the more things change, the more they stay the same. If the rest of the country caught a cold during the recession, African-American communities caught pneumonia, and are far from recovering.

The persistence of disproportionate African-American unemployment is a capstone of the “heads-they-win-tails-we-lose” persistence of African Americans getting the worst when the economy declines and the least when the economy grows.

That pattern was repeated during the Great Recession. An essay on the black middle class in the National Urban League’s “State of Black America 2012″ report contains some of the stark details, concluding that “almost all of the economic gains of the last 30 years have been lost” since late 2007, and worse, “the ladders of opportunity for reaching the black middle class are disappearing.”

In 2010, the median household income for African Americans was 30 percent less than the median income of white households 30 years ago. African-American household income fell more than 2.5 times farther than white household income during the Great Recession, 7.7 percent versus 2.9 percent. Home ownership rates also fell for African Americans at roughly double the rates of whites, essentially wiping out the gains in home ownership since 2000. Today, more than a quarter of African Americans live below the poverty line, compared to about 10 percent of white people.

A newly released report by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies also underscores the severity of economic conditions among African Americans. That report focused on black unemployment rates in 25 states with large African-American populations starting when the economy was at its peak in 2006. “In 2006, prior to the recession, the unemployment rate in the black community was already at recession levels in every one of the 25 states we studied, from 8.3% in Virginia to 19.2% in Michigan, and in 20 of the 25 states the unemployment rate for African Americans was above 10%,” the report said. “In 2011, more than two years after the economic recovery began, unemployment rates for African Americans across most age, gender and education categories remained significantly higher than their pre-recession rates.”

In fact, the jobless rate for African Americans between the ages of 20 and 24 in these states was 29.5 percent in 2011, two years after the recession had supposedly ended.

“If the national unemployment rate was anywhere near these percentages, we’d be in crisis emergency mode,” said Ralph B. Everett, president of the Joint Center, during a discussion of the report last week.

Instead, the “crisis” that has the attention of the Washington political class is the federal debt, and even the Obama administration has now caught some of the fever. This fixation dictates that the federal government not be able to devote the resources necessary to address this crisis. While members of the “Fix the Debt” crowd – overwhelmingly white and disengaged from the day-to-day struggles of African-American communities – pleads concern about the debt that will be handed down to their children, no one speaks of the consequences that the continuing economic depression experienced by millions of African-American households will have on the next generation.

Coming at the same time President Obama's budget, the State of Black America 2013 report raises the question of whether President Obama has done enough to address the economic realities African Americans are facing. It's a fair question, given that the overwhelming majority of African-American voters backed Obama and the Democrats in 2012. For its part, the administration touts its economic efforts on behalf of African-Americans, which Rev. Al Sharpton summed up in what should be forever known as the "ham sandwich" approach to Black economic concerns.

At that White House meeting, which lasted more than two hours on Feb. 21, the Rev. Al Sharpton, president of the National Action Network, drew laughter from Obama and his fellow activists when he found a folksy way to defend the president from charges he didn’t talk enough in his first term about black issues:

“I had a friend when we were in school who told me he was going on a kosher diet. He converted his religion. We went to eat, and he ordered a ham sandwich. I said, ‘You can’t eat that.’ He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘That is pork.’ He said, ‘No, no, no. Pork is pork chops or pork loin. I said, ‘No, you don’t have to call it pork for it to be pork. It is still pork.’ ” The lesson, Sharpton said, is simple: “Some things he’s done, it may not have been called ‘black.’ But it affected us. It was still pork.”

With due respect to both the president and Rev. Sharpton, Black American stands at an economic crossroads. Depending on the course taken from here, the gains of the past 50 years — even those of the past 150 years — will either be the foundation that future gains are built upon, or they will be weathered away by winds of economic disasters. African American Economist Bernard Anderson points out that President Obama would do well to remember the words of another Democratic president.

Anderson still recalls from memory Johnson’s stirring speech at Howard. “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up the starting line of a race, and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair,” LBJ said. Anderson pointedly asks, “Can you imagine President Obama referring to 200 years of slavery? I cannot imagine him saying anything like that.... He has an obligation to address this [economic disparity] that is grinding black people down.” While encouraged by parts of Obama’s State of the Union address, Anderson asks, “Why has he not revisited the issue since he made that speech during the campaign?”

It's necessary to go even further back in history to understand the nature of the economic state of Black America; not just 50 years, but perhaps even back 150 years to the Emancipation proclamation.

In his book, Ending Slavery: How Well Free Today’s Slaves, scholar expert Kevin Bales describes the steps he believes are necessary for communities and countries all over the world to end the modern-day slave trade - from sex-trafficking to forced labor in jungles of Brazil to bonded labor passed down through generations in India. Key among those steps is the rehabilitation of freed slaves. Emancipation, Bales says, is insufficient without investment in rehabilitating freed slaves, who require medical care, education, and reorientation of their skills, which he describes in New Slavery: A Reference Handbook, as "restor[ing] the personhood of the person."

The essential condition of bondage is in the minds of the people. ...They have been conditioned to accept that their place is at the periphery of society. The process of release and rehabilitation is to restore the personhood of the person, to restore self-esteem, confidence, and the feeling that they too can win.

He goes on in Ending Slavery to describe how that process stopped short in America, after the Civil War.

After the American Civil War freed slaves also knew what it would take to build a decent life in free dome. Their work experience told them that forty acres and a mule could feed a family and grow enough of a cash crop to make a life and get the children to school. American slaves never got their forty acres and a mule.

Without collective investment in rehabilitation and restoration, Bales writes that many freed slaves return to slavery, either by choice or compelled by circumstances unchanged except for simply having been released.

It would take another post or two to thoroughly address, but from 1863 to 1963 to 2013, American as stopped sort of addressing the economic needs and realities unique to African Americans. That's probably because those needs stem from a history that seems to have gotten more difficult to talk about, instead of easier. It's one of the ironies of having a Black president. And it may be what's keeping Obama from speaking out about the economic crisis in Black America, and proposing policy solutions that speak directly to that crisis.

President Obama's misguided, deal-seeking budget is, as described by the White House, "not ideal." Lacking the bold jobs plan he introduced in 2011, it doesn't amount to a "ham sandwich" for African-American families and communities still waiting for recovery.

In my mind the psychological effects of slavery are what take me down every time, it robs me of my self esteem and without that I don't think o a higher plane.