One hundred and fifty years ago today, 12 weeks after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, The Nation magazine was born and immediately called for President Andrew Johnson to exercise his power and enshrine "the right of the negroes to the franchise."

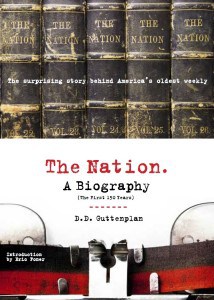

I know this thanks to the wonderful book published today, "The Nation: A Biography (The First 150 Years)" in honor of the magazine's 150th birthday. The book is available in e-book and paperback for $9.95 at TheNation.com/ebooks.

The book, written by the magazine's London bureau chief D. D. Guttenplan, is a journey through the history of post-Civil War America seen through the lens of the American left. And it's a reminder how commentary, criticism and dissent have constantly shaped our nation's history.

I had the chance to interview D.D. Guttenplan about his sweeping work, and what he learned culling the decades upon decades of back issues. Our exchange is below:

Q. After reviewing 150 years of The Nation, how would you sum up its contribution to American democracy?

Guttenplan: In the very first issue, published on July 5, 1865, I found an editorial that declared: “The tide is turning in favor of liberalism with resistless force…. We utter no idle boast when we say that if the conflict of the ages, the great strife between the few and the many, between privilege and equality, between law and power, between opinion and the sword, was not closed on the day in which Lee threw down his arms, the issue was placed beyond doubt.”

Of course that struggle between privilege and equality—what today, borrowing from the Occupy movement, we might call the 1 per cent and the 99 per cent—still rages. But from the very first The Nation has always made clear what was at stake. And I think that has been the magazine’s greatest contribution to democracy through the decades.

During Reconstruction the question was whether we would truly redeem the broken promise of Jefferson’s language in the Declaration of Independence—and sadly both the country and The Nation decided that redemption could be postponed—with tragic consequences we continue to reap from Staten Island to Charleston.

In the 1890s, when America succumbed to the temptations of Empire, and crushed the popular revolt in the Philippines that we had encouraged to throw of Spanish rule, The Nation’s founding editor, E.L. Godkin, wrote that “the question is not ‘What are we going to do with the Philippines?’ but ‘What the Philippines is going to do to us?’”

When Woodrow Wilson told the country that World War I was being fought to make the world safe for democracy—and then agreed to peace terms at Versailles that served British and French imperial interests at the expense of subjugated peoples in Africa, India and the Middle East, The Nation made it clear that this, too, was a betrayal that would have consequences.

When Martin Luther King, Jr., who wrote an annual report for The Nation on the state of civil rights in America, summoned the country to make that “last steep ascent” to economic justice in our pages, he was again seeking to redeem the promise of democracy.

And when, after the September 11 attacks, Jonathan Schell called for “a just response” the magazine was again serving as a witness to democratic, rather than imperial, values.

Q. More specifically, are there articles that you found that directly impacted the course of history?

Guttenplan: Although The Nation has often taken radical positions, those positions have often been vindicated by history. But in a direct way, as I write in The Nation: A Biography, the magazine’s campaigning editorials, which urged Republicans to desert their own party, probably swung the 1884 presidential election for Grover Cleveland, whose margin of victory in New York—the state that put him over the top—was just 1,149 votes.

Andrew Kopkind’s historic unsigned editorial in 1988 endorsing Jesse Jackson didn’t of course swing that election. But it did lay out the reasons why Jackson’s candidacy deserved to be taken seriously—and was not only extremely influential on the left at the time, but arguably helped pave the way, as did Jackson’s candidacy, for Obama’s election two decades later.

And of course New York’s current Mayor Bill de Blasio says his victory wouldn’t have been possible without The Nation’s endorsement.

But most of our impact has been outside the field of electoral politics. Oswald Garrison Villard, who turned The Nation from the house organ of the Republican Party to the liberal/radical journal it remains today was a founder of the NAACP and a dedicated campaigner for women’s rights.

Freda Kirchwey, who followed him, not only was a model of a working woman intellectual—she made The Nation a crucial voice in persuading the country that the fight against fascism and Nazism was America’s fight.

Her successor, Carey McWilliams, stood practically alone against the tide of McCarthyism and reaction; he also published Bernard Fall, who argued for a negotiated end to the war in Vietnam—in 1954! McWilliams also printed Ralph Nader’s first article “The Safe Car You Can’t Drive,” which launched the consumer movement.

Victor Navasky opened The Nation’s pages to arguments for feminism, gay rights, and an end to nuclear weapons. And though he lost the case at the Supreme Court, Navasky also fought for the principle—which I believe will someday be vindicated—that a president’s record belongs to history, and the people, not to whichever publisher pays for it.

In our own time Katrina vanden Heuvel has made The Nation a voice for sanity in relations with Russia, fought a lonely, but prophetic, fight against the invasion of Iraq, opened the magazine to the full spectrum of opinions on Israel, Palestine and the Middle East, and nurtured and encouraged a whole new generation of young activists in campaigns ranging from Occupy Wall Street to the Fight for Fifteen to #BlackLivesMatter.

With any luck The Nation will be helping to bend the long arc of the universe towards justice for decades to come.

Q. What one thing stands out that The Nation got right but most contemporaneous commentators did not?

Guttenplan: That becoming an empire would have a toxic impact on our democracy.

We were right about that in the 1880s, when we opposed the annexation of Hawaii (and got vilified by Theodore Roosevelt), and in the 1890s when The Nation joined with Mark Twain and others to found the Anti-Imperialist League opposing the conquest of the Philippines, and in the 1920s when The Nation sent James Weldon Johnson (author of "Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing”) to report on the occupation of Haiti.

And we remained prophetic (and in the minority) on the conquest of Guatemala and the Dominican Republic, the war in Vietnam, and our continued depredations in Haiti, as so ably reported by Amy Wilentz. Not to mention the magazine’s long and honourable record on Cuba.

Q. And, with hindsight, what one thing did The Nation get most wrong?

Guttenplan: There are two great stains on The Nation’s record: one is the way the magazine deserted African-Americans in the 1870s and 1880s in the interest of political expediency and as a result of a notion of liberalism that limited itself to free trade and free speech.

The other was the magazine’s hostility, from the 1870s to just before World War I, to the labor movement. Although the abolitionists who founded The Nation believed in free labor, many of them were patricians who were both frightened and offended by the rising assertiveness of workers.

Probably the lowest point on this issue was The Nation’s editorial on the Haymarket martyrs, which complained that in allowing two of the condemned to escape death the state of Illinois was encouraging “social pests” who promise a great revolution “in which we shall all lie on our backs and make machinery do our work for us,” and who claimed that “the present distribution of property is in the main the result of cheating.”

It’s a long way from there to enthusiasm for Elizabeth Warren and the Fight for Fifteen, but we got there in the end.

Q. What parallels do you see with The Nation's tangles with past Democratic presidents -- such as Wilson, Roosevelt, Kennedy -- and the friction that has arisen with living Democratic presidents Clinton and Obama?

Guttenplan: As should be clear by now The Nation began as an organ of the Republican party—and tangled with Republican as well as Democratic presidents, scoring Cleveland for encouraging imperialism and attacking Wilson on race and on his broken promise of a “peace without victory”—or secret treaties—after World War I.

But it is in the magazine’s nature, as a believer is social movements rather than political messiahs, to be disappointed with actually existing presidents.

Personally I wouldn’t lump together Clinton—who attacked Sister Souljah, and hastened back to Arkansas to execute the retarded Ricky Rector—and Obama, where the relationship seems to me more reminiscent of The Nation’s and Freda Kirchwey’s relationship with Franklin Roosevelt: FDR was continually trimming his sails in response to changing political winds, and The Nation gave him hell for it. But the magazine also rightly expected more of him than of other presidents, and helped to build and embolden the social movements which forced FDR to deliver on at least some of his most radical promises.

At its best the magazine’s relationship with President Obama has been similarly grounded in high expectation, and although there have been disappointments and even arguably (as in the case of TPP) betrayals, the conversation has remained civil.

Q. What was it like for you to look at 150 years of history through the perspective of The Nation?

Guttenplan: Reading through the Nation’s history—which is also the history of our movement and our country—has been an ongoing revelation.

As a historian I was still stunned by how often themes and arguments—whether on the role of the police, or the right to privacy, or relations between men and women—recur in our history.

For those of us on the left I think it’s particularly important to reconnect with our history, to remember that we built this country, and to realise that the legitimacy of our ideals and our cause is as deep and as venerable as any championed by those who claim the mantle of “conservatives.”

We are radicals not only because we believe that root and branch change is needed to bring justice, but also because we believe that, at root, those are the values that Americans have fought for since the Boston Tea Party.